New Course Spotlight: Human Rights in the 20th and 21st Centuries

When CRMS seniors enrolled in classes this year, there was a new history course offering from Beth Krasemann, the most recent addition to CRMS’s history faculty.

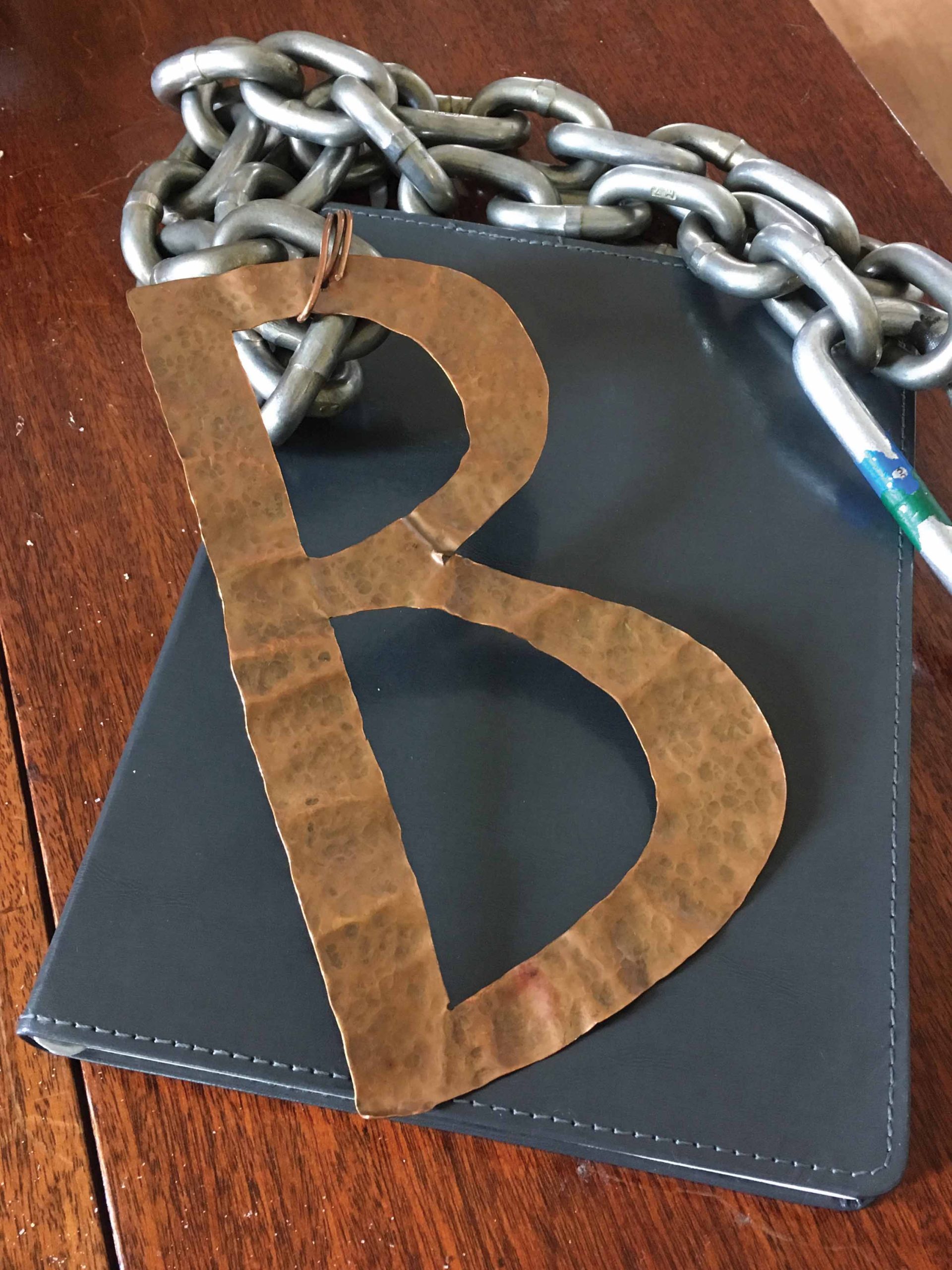

Beth and her husband, Volker, joined the CRMS faculty this fall, moving to Carbondale after multi-decade careers teaching history and science, respectively, at boarding schools back East. Beth hit the ground running both literally (as a coach for the CRMS cross country team) and figuratively (designing and implementing a new 12th-grade history course).

Beth’s new history class, Human Rights in the 20th and 21st Centuries, prompts students to question their values and actions as they consider the development and protection of human rights over the past century as well as the multifarious and ongoing threats to those rights.

Beth will be the first to tell you that history doesn’t settle in the past. She elaborates, “history is now.” Passion for justice and social change electrifies her voice when she talks about her course material, explaining how she wants her students to understand that their engagement and their actions matter. “History happens because people act or don’t act,” Beth says.

People who do the right thing can change the course of history for the better, a lesson that students have come to appreciate this fall as they’ve surveyed case studies of 20th-century genocides. The list of genocides studied includes the Herero genocide in what is now Namibia (1904-08), Armenia (1915-17), the Holodomor in Ukraine 1932-33), the Holocaust (1941-45), Cambodia (1975-79), Rwanda (1994), and Darfur (2003-). A daunting, distressing, and dispiriting list, to be sure, but Winston Churchill’s famous maxim comes quickly to mind: “those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.”

Beth hopes for her students to connect the lessons from history to their own lives and consider how they will act in the face of injustice.

Human Rights in the 20th and 21st Centuries examines the conditions that give rise to genocide and the systems of government that allow for those conditions to develop in the first place. But as an inquiry-based course, Beth doesn’t give students any answers. Instead, she poses questions grand in scale, like “How should countries balance the rights of the nation with those of the individual?” and “How should the world community address human rights violations in other nation-states?” She also asks questions pertinent to the immediate lives of her students, like “How does your name contribute to your identity?” and “What makes a person good?”

In a recent unit, students looked at a variety of psychological and behavioral studies to better understand prototypical human reactions. Why, for example, did volunteers selected to be “guards” in the Stanford Prison Experiment use increasingly brutal force against the volunteers selected as “prisoners” despite receiving no such instructions to do so? And why, in 1964, when Kitty Genovese was murdered outside her apartment in Queens, did the New York Times claim that numerous witnesses saw or heard the attack but failed to come to her aid (an incident used to later define the “bystander effect”)?

Though most of us would both choose and hope to be outliers in these examples, there seems to be a historical and psychological precedent for instinctive conformity and compliance. Human Rights in the 20th and 21st Centuries examines how easily people can be swept along in the horrors of genocide without protest or resistance, but it also identifies people and moments in history that have stood up against these forces.

According to CRMS senior Maya Menconi, the class encourages students to be “conscientious about the patterns of human tendencies and how to spot these signs and patterns” before a situation deteriorates. Maya explains that taking action and avoiding groupthink and a bystander mentality are driving principles of the course.

It is not unusual for Beth to ask her students what they would do if they found themselves in a particular situation (acknowledging that their answers likely reflect their ideal theoretical reactions).

The course weaves together stories of individual and collective acts of resistance with the dark histories of genocide. By shining light on “upstanders,” people who stood up for human dignity in the face of tremendous pressure and dangers, Beth hopes that her students will recognize their own potential to make the world a better place.

Like the best humanities courses, Beth’s Human Rights class promotes deep analysis leading to self-reflection. This self-reflection comes at a critical time in the lives of Beth’s students as they explore the dimensions of their own moral compasses and are poised to embark on their collegiate and life journeys.

MYCRMS

MYCRMS

Virtual Tour

Virtual Tour