If Any River Is Wild and Scenic, It’s the Crystal (Colorado)

This is reprinted from the American Whitewater Journal March/April 2023 edition.

By Kayo Ogilby

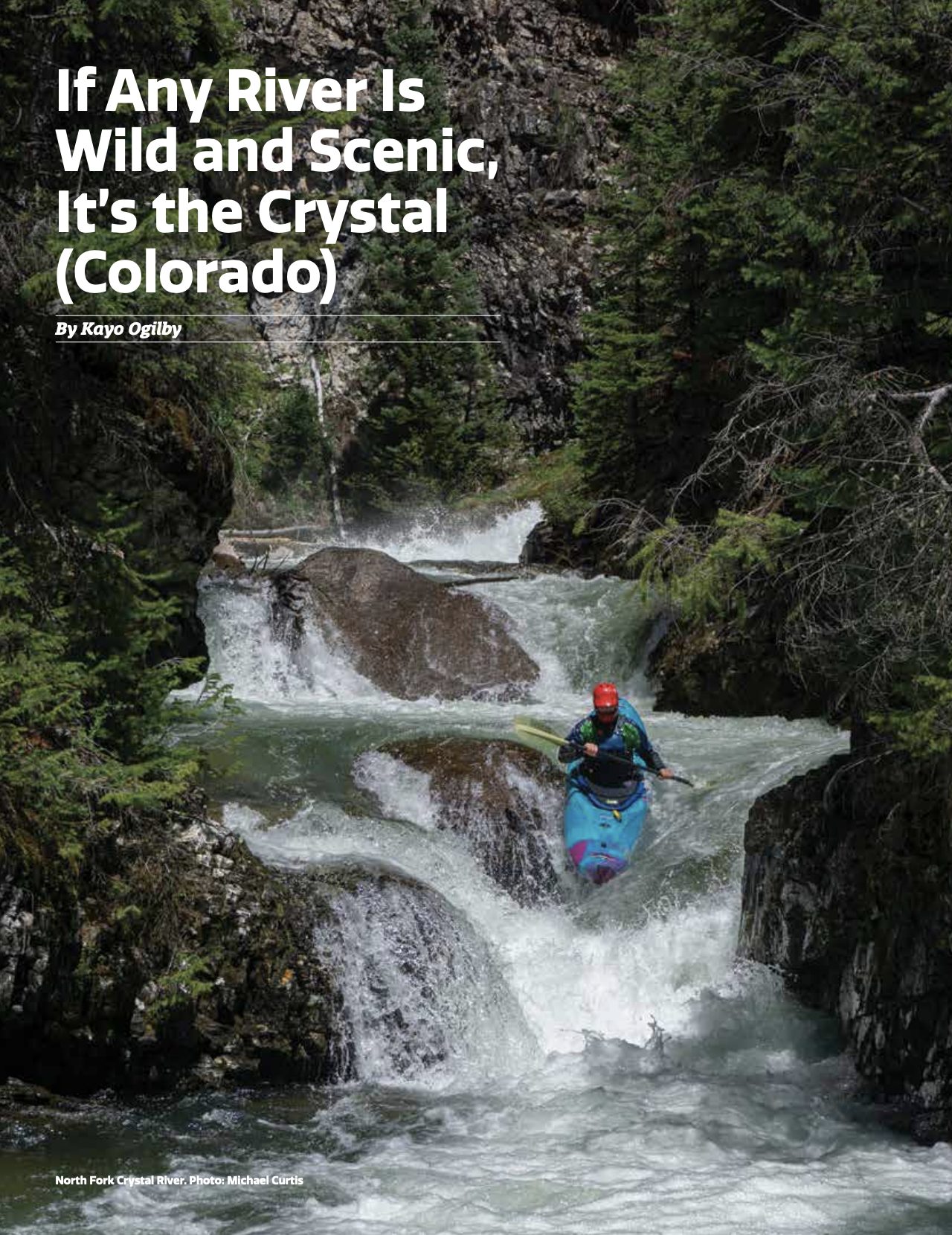

As American Whitewater familiarized itself with the push for a Wild and Scenic Crystal River designation, I quickly learned of four community pillars of that effort, one of whom is named Chuck Ogilby, river defender and owner of Avalanche Ranch Hot Springs. Later, at a board of trustees meeting in my community of Carbondale, a municipality that sits along and depends on the waters of the Crystal, I heard his son, Kayo, speak about the importance of a free-flowing river with an eloquence that can only come from deep love and connection to a place. I was hoping to include a story about the Crystal River in this edition of the Journal and was ready to write one based on my own love of my backyard river. We are kicking off a robust discussion with stakeholders of all backgrounds this year to determine if a Wild and Scenic designation is feasible for the Crystal River. I felt it timely to share with our whitewater community about this special place. However, when I heard Kayo speak, I knew his story, and that of his family and students could more thoroughly describe all that this wild river provides to those who play in it, learn about it, and depend upon it. Please enjoy as Kayo takes us on a journey down the Crystal Narrows at healthy flows and meet his family and friends along the way.

– Hattie Johnson, Southern Rockies Stewardship Director

DAPPLED MORNING LIGHT SPILLS THROUGH THE LIGHTLY shivering cottonwood trees that tower over the main house of Avalanche Ranch as I turn in the steep gravel driveway and pull up in front of the reception desk and store. My nephew, Fisher Jacober, and another Colorado Rocky Mountain School (CRMS) student, Beck Jennings, are already in their kayak gear and grinning mischievous grins while making a display of looking at their watches as I pull in, always ready to rib me for being late. CRMS alumnus, whitewater aficionado, river steward, and former American Whitewater staff member Angus Harley soon pulls in behind with his signature grin that transcends the confines of his face. After a delightful reunion of hugs and introductions, boats are thrown in the back of the Jacober pickup, and we make the quick bump up to Penny Hot Springs, the illustrious put-in for the Narrows section of the Crystal River.

DAPPLED MORNING LIGHT SPILLS THROUGH THE LIGHTLY shivering cottonwood trees that tower over the main house of Avalanche Ranch as I turn in the steep gravel driveway and pull up in front of the reception desk and store. My nephew, Fisher Jacober, and another Colorado Rocky Mountain School (CRMS) student, Beck Jennings, are already in their kayak gear and grinning mischievous grins while making a display of looking at their watches as I pull in, always ready to rib me for being late. CRMS alumnus, whitewater aficionado, river steward, and former American Whitewater staff member Angus Harley soon pulls in behind with his signature grin that transcends the confines of his face. After a delightful reunion of hugs and introductions, boats are thrown in the back of the Jacober pickup, and we make the quick bump up to Penny Hot Springs, the illustrious put-in for the Narrows section of the Crystal River.

This morning, like most mornings, bighorn sheep are grazing along the river directly across from the hot springs. This time of year, the runoff has inundated the hot springs proper, but a glance upstream reveals the backlit steam escaping from the multiple hot vents of Filoha Meadows. This preserved nature park and open space protects this unique geothermal area at the base of Mt. Sopris and is home to unique plant species such as the Stream Orchid, as well a vestigial pocket of firefly species whose genetic underwriting has agreed for millennia with the year-round warm wetland grasses in this geothermal pocket.

As we drag our boats down the embankment from the parking lot, Fisher and Beck, who are students in my geology class at CRMS, lob a question with the intent of tricking me into divulging the answer to the current field problem they are working on. I’ve asked them to determine whether or not Mt. Sopris, the icon of the lower Roaring Fork and Crystal valleys, is a volcano. Angus, who is on the other side of this geologic conundrum, slides me a sly glance. He knows that the constriction in the Crystal River canyon that creates the tumultuous freight train of classic Colorado roadside Class IV whitewater is there because of the river’s attempt to incise through the 34 million-year-old granite of Mt Sopris. While the words written in those rocks speak a molten and igneous narrative, it is a story of a body of magma that cooled at depth rather than exploding onto the earth’s surface. As much as it looks like one, Sopris is not a volcano.

Many students get tricked each year by the big black basaltic boulders strewn in and around the granite of Penny Hot Springs. These lava rocks are of human origin, however, and were rolled into the hot springs by the angry landowner of Filoha Meadows in the 1980s in an attempt to obliterate the hot springs due to his dislike of naked hippies exposing themselves to his cows grazing on the other side of the river. There is no stopping scantily-clad hot water lovers, and soon the pools were re-excavated through the new debris, and these boulders now provide a punctuated anthropogenic feng-shui to the Penny geothermal experience.

The explosive and tumultuous mayhem of whitewater that is the result of the acceleration of the Crystal River as it is forced through the Mt. Sopris constriction has its own eruptive sig-nature. The group’s geologic curiosity quickly dissipates as our senses are directed to the immediacy of the task in front of us. Paddling ahead, we are shot into the cataclysmic and explosive whitewater that is the Narrows proper. Intriguing surf ferries and boofs into boiling micro eddies that looked doable from our road scout suddenly became an ephemeral question mark. A combination of the wave size (waaaay bigger than it looked from the road), speed of the water (waaaaay faster than it seemed from the road), and the blinding white of morning backlit 48-degree snowmelt water all conspire to turn mapped-out moves into small craft improvisation.

The improv reaches its crescendo in the Lower Narrows, where the river widens into a labyrinth of pour-overs that put directional strokes and braces to the test. Eddies are almost completely absent through here, making swims long, abusive, and hair-raising. The boys do a fine job choosing their own lines and establishing quick, smiling visual check-ins as the group flies through this section Blue Angel style.

The river soon makes a sharp left turn which presents us with the first braided channel, and we choose left. It requires an awkward move over a downed tree that has fallen from Tim and Cindy Cole’s property. Tim, a giant bear of a man with a handlebar mustache, is in the yard walking toward his blacksmith studio. After a lifetime as a coal miner in Redstone, he found peace in the journey of becoming a master blacksmith, most notably crafting Damascus steel jewelry, as well as finding ways to bring intricate and subtle detail to unlikely pieces of blacksmithed art. A steel rose sits in my parent’s living room as an example of one of my favorite pieces of his work.

Just below their house, we float past the tributary of Avalanche Creek, our family’s favorite low-water fishing hole. As we float by, an image of Fisher, age 7 or 8, learning to drift a nymph with his new birthday fly rod under the tutelage of my dad, Chuck Ogilby, known as Papa to his grandchildren, finds its way out of the archives of my memory.

My dad is a nymph fisherman. He has always been a firm believer that flyfishing should happen below the surface, down where the big fish lurk and do the bulk of their feeding. He perfected this art long before the days of strike indicators. Learning from him was a task of learning how to manage one’s line in a way that it could be kept taught enough to “feel” the difference between a strike and the bottom, all while maintaining a natural drift. As a young and aspiring but impatient fly fisherman, I failed for years in my attempts to grapple with my dad’s type of fishing. It was visceral and sophisticated and required a level of zen that eluded my teenage self. The visual cues that dry flies and strike indicators provide were completely absent from his approach. My dad can feel rivers. He can feel trout. He can feel the details of the benthic topography. And as a result, he could find fish that others missed or simply didn’t know existed. This journey led to a love affair with Western rivers, and a recognition, in the early 1970s, that they were threatened. And so began his path of fighting for them. Living in Vail at the time, he threw the bulk of his efforts at fighting trans-mountain diversions and the Denver Water Board from pulling water out of Western Slope rivers and piping it to the rapidly developing Front Range. His home waters then were Gore Creek and the Eagle River. Today they are the Crystal and Roaring Fork, and the well-being of these rivers, specifically efforts to get the Crystal federally designated as Wild and Scenic, have become his primary battle fronts.

This type of fishing, and a passion for free-flowing rivers, would cross my path again many years later through the lens of another CRMS student, Martin Gerdin. Martin returned to CRMS as a resident glassblowing artist, where he would both pursue his own art and help teach the art form he had fallen in love with while attending the school. He started dabbling with blowing glass fish at about the same time that he discovered fly fishing. Martin is a visionary. He is one of those individuals who quickly sees beyond the confines of the convention of any given discipline and is soon charting his own path. The beauty of this is that he would never describe himself as a natural student.

He was plagued with learning challenges and struggled in the classroom. He has become one of many reminders for me, as an educator, that success in a conventional learning space is not an indicator of intelligence, ingenuity, creativity, and drive. Once he started, Martin quickly became the best fly fisherman I have ever witnessed. And I have been surrounded by master fly fishermen my whole life.

He fished the way my father fished, below the surface. I once watched him catch 26 fish within an hour, his black lab splashing every which way, in the world-famous tailwaters below Ruedi reservoir on the Fryingpan River–waters that most fly fishermen find elusive and challenging. Fishermen who had traveled from far and wide watched this spectacle, asking him what he was using, which he would share with enthusiasm. He soon had us all using the same flies. I think I caught two fish that day, for which I was thrilled, but none of us could feel the water, the bottom, the fish, like Martin could.

He is the type of fisherman who invented his own system of fly-line and leaders because there was nothing out there in the industry that quite fit what was in his mind’s eye. In no time, he was pulling fish out of the Crystal River that were encroaching on state records. At the same time, he began mastering his niche as a glass artist.

He figured out how to blow glass fish with enough accuracy and detail to match species all over the world, something no one else was really doing in the glass world. He was constantly trying to figure out what technique would allow him to bring something like an accurate camouflage pattern to a brook trout. He would bring his fish into fly shops and trade them for fly fishing equipment. Word spread across the fly fishing world. If you wanted a masterful piece of glass art of your favorite home water fish, Martin was your guy. Now you have to get in line to get one of his pieces of art.

If it came down to choosing between fishing the Fryinpan or the Crystal on any given day, Martin chooses the Crystal. “It’s a freestone river. It is not dammed at any point of its journey. This has become a rare thing for rivers in the West, and the watershed, therefore, still holds on to some vestige of its original state. The very core of who I have become as an artist and fly fisherman is predicated on the well-being of this river.”

Below Avalanche Creek, the Crystal widens and relaxes a little bit. We’ve dropped our guards in this stretch and swapped our vigilance with a playboating radar as each of us engages in the more playful decision-making process of whether to kickflip waves presented to us or catch a surf on the fly. There are plenty of micro eddies, holes to boof, and moves to make as each paddler paints with their own pallet through this section.

We pass under the Avalanche Creek bridge and past Avalanche Ranch–the hot springs and lodge where my sister Molly and our parents have used the geothermal water associated with Mt. Sopris as a means of living. My dad endlessly oversees the hot water, my mom runs the antique and gift store, Molly manages the lodge and hot springs, and her husband Tai raises grass-fed beef in pastures of the lower Crystal River Valley.

Tai is a believer that most landscapes have evolved with hoofed ungulates and, if done right, cattle grazing can enhance grass ecosystems rather than degrade them. He and his brothers, and now his two children Fisher and Phia, have chased that vision through their enterprise, Phoenix Ranching. They also use these cows as their source of meat for Fat Belly Burgers, a small farm-to-table burger joint on the west end of Mainstreet in Carbondale.

Fisher’s grandmother, Francie Jacober, a retired lifelong teacher, manages the restaurant. When she is not doing that, she serves as a Pitkin County Commissioner. It would not be many weeks after we paddled this stretch before I would witness Francie take the lead on presenting a comprehensive case to the Carbondale Town Council to get the town’s support in fighting for the federal designation of the Crystal River as Wild and Scenic. Doing so would forever preserve it from potential future dams and diversions. It is in these underattended and quiet public meetings, and the time before and after, where the true labor of making a difference happens.

I am again reminded of this several weeks later as Chantel Hope and Grayson Voorhees, the student leaders of the CRMS environmental club, organize a meeting at the Bluebird Cafe in Glenwood Springs to zoom with newly elected District 57 Colorado representative Elizabeth Velasco and state senator Dylan Roberts. They meet to discuss what environmental issues and bills the two representatives are advocating for in this session of the state congress. The meeting is small–four or five other people beyond the club are there. I am inspired by this group of students’ eagerness to engage and find their way into the political spaces where action can occur, which will culminate in a trip to the capitol in April to lobby senators on bills and issues that they are passionate about.

On this night, the issue that catches my ear is Velasco’s intention to take on water inequality that is felt by multiple trailer park communities, which serve as critical employee housing in the ever more expensive housing crunch in mountain valleys. There are no processes in place to guarantee that this type of housing has safe water. It’s the wild west in this regard, and it plays out as one more significant barrier for working communities–often communities of color–to navigate as they try to make ends meet across Colorado. It’s a messy situation, and the work is hard, slow, complicated, and in desperate need of attention.

At these flows, it’s not long before we eddy out at the marble slab. This is one of a multitude of marble blocks that were dumped into the riverbed from trains hauling marble down from the Yule Creek Marble Quarry in the mine’s early history. This may be the only place on the planet where a kayaker can cartwheel or stern squirt, a feature created by a slab of pure marble.

These marble dumps are now historical landmarks, and the uniqueness of this stretch of river catalyzes conversation about the upper headwaters of the Crystal as we float through some of the boogie water below. Fisher and I find ourselves comparing notes on our last backpacking trips upstream of the town of Marble. I had finished a 10-day wilderness orientation trip with a group of seven new CRMS students in Marble. Our route had started at Maroon Lake in Aspen and wove our way past Geneva Lakes, past Silver Creek, and into the upper reaches of the Crystal. The year prior, Fisher had connected a route up Avalanche Creek, to Capital and Pierre Lakes, and out to Marble. That year CRMS had been unable to conduct its normal wilderness orientation because of Covid, so his parents just created an experience and route of their own. We soon discussed our favorite nooks and crannies, geologic oddities, and new terrain we had seen on those trips.

Downstream of BRB Resort, the river opens up into a floodplain that cuts through glacial outwash terraces, recording the last four glaciations of the Pleistocene. These terraces provide the first significant agricultural space in the Crystal River watershed and, with them, the first irrigation diversions in the form of wing dams. Late in the summer, this stretch of water, just above the fish hatchery, becomes almost devoid of water. It is here where the big questions overtly and visually manifest themselves. The dance between human use and the well-being of a fluvial ecosystem is laid raw and exposed.

A few short months after that morning’s spring paddle, I would get an email from my sister Molly, directed to all of Fisher’s teachers, letting us know that he would be late to school that day, and she wasn’t quite sure what time he would get there. He had shot his first elk, it had been an all-night journey of packing it out of the high country, and now they were in their kitchen shoulder-deep in butchering elk.

Why do we choose to live in the West? We, or someone in our family’s lineage, were drawn to something raw and gritty. A free-flowing river and the way the morning light danced off its water grabbed our soul and wouldn’t let go, an alpine meadow high in a cirque where the silence hung along with the last of the alpenglow. Our access to these spaces feeds us, both figuratively and literally. It’s in these spaces where we make our art, draw our deepest connections with each other, and put our demons to rest. It is also in these spaces where we quite literally make our living. Ecologists would label these spaces as providing “Ecosystem Services.” Without our protected, treasured, and preserved wild spaces, the paychecks in the West would quite literally dry up.

As more and more of us come to the West for the same reason, we run the risk of trammeling and losing the very treasure that brought us here in the first place. So we must find in our lives as Westerners a circular path. First, as Ed Abbey would say, “Get out there and hunt and fish and mess around with your friends, ramble out yonder and explore the forests, climb the mountains, bag the peaks, run the rivers, breathe deep of that yet sweet and lucid air, sit quietly for a while and contemplate the precious stillness, the lovely, mysterious, and awesome space. Enjoy yourselves, keep your brain in your head and your head firmly attached to the body, the body active and alive.” Then come back to work and sustain our families. And then find time to fight for the spaces we cherish and in so doing, partake in this great experiment of democracy. Then, get back out there and play.

My dad, along with other dedicated river stewards, has been working to designate the Crystal River Wild and Scenic for years. It is time to finally provide this river with the permanent protection it deserves.

MYCRMS

MYCRMS

Virtual Tour

Virtual Tour